Joseph Bannor Kunimyelor and the Chorkor Jazz

CHORKOR JAZZ BAND

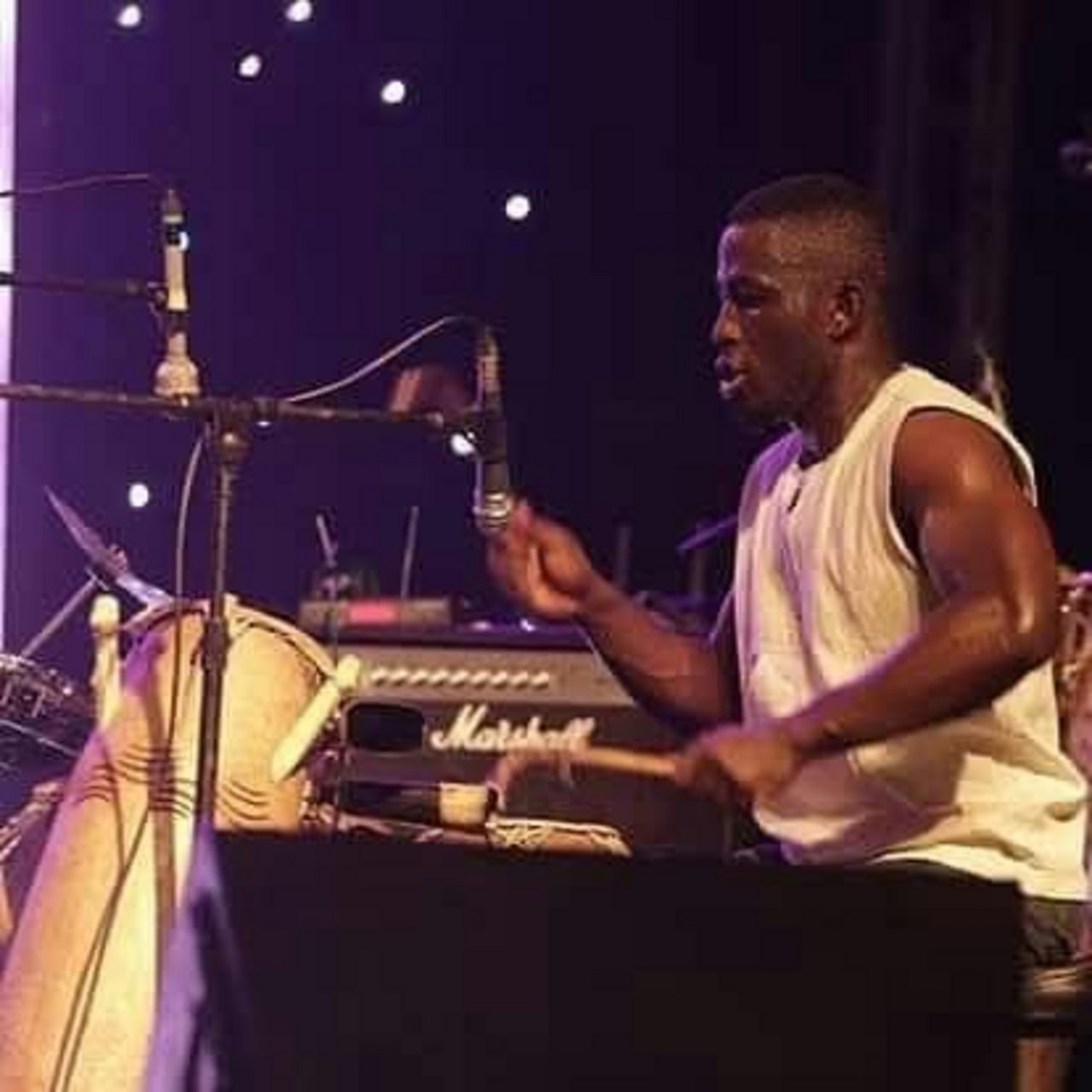

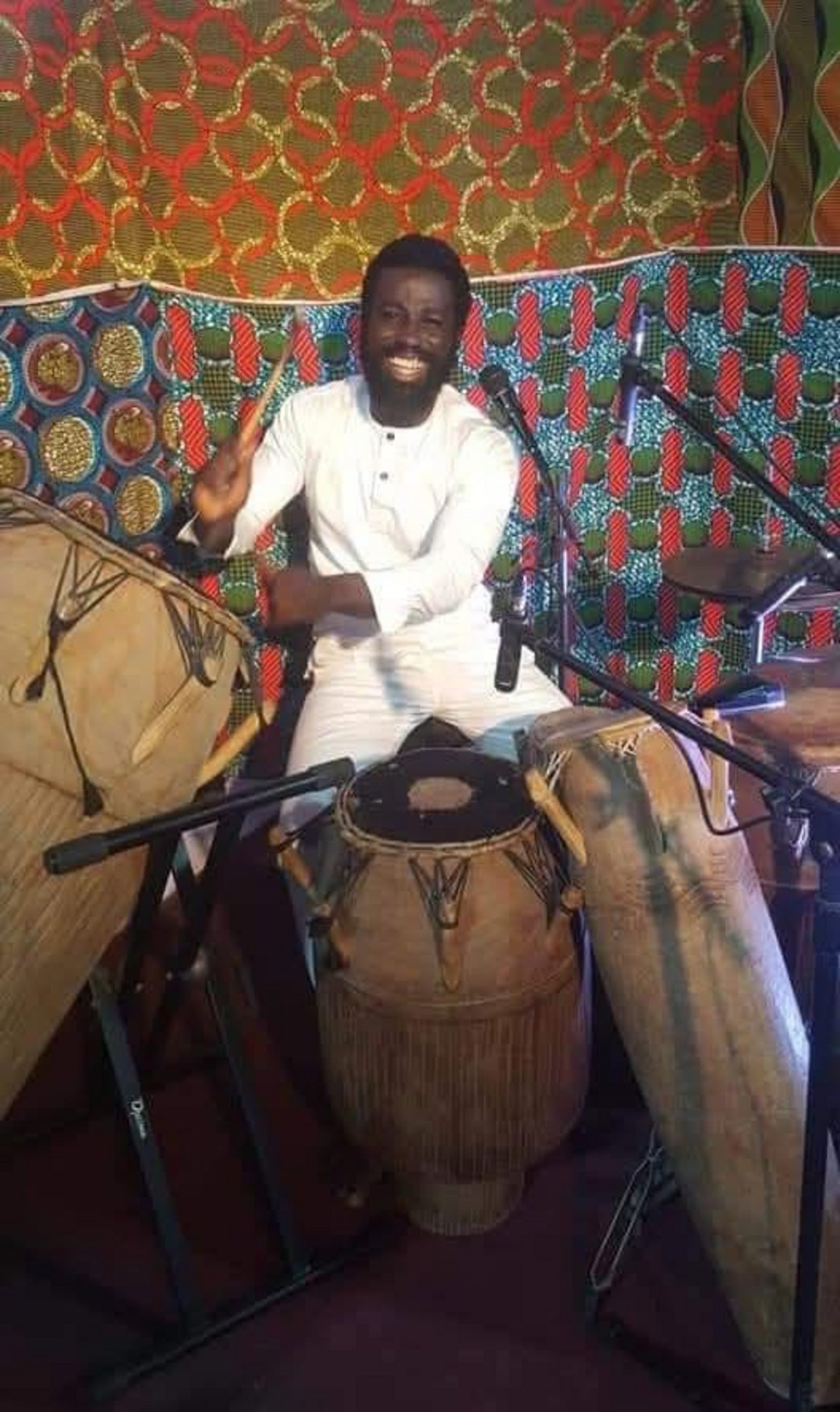

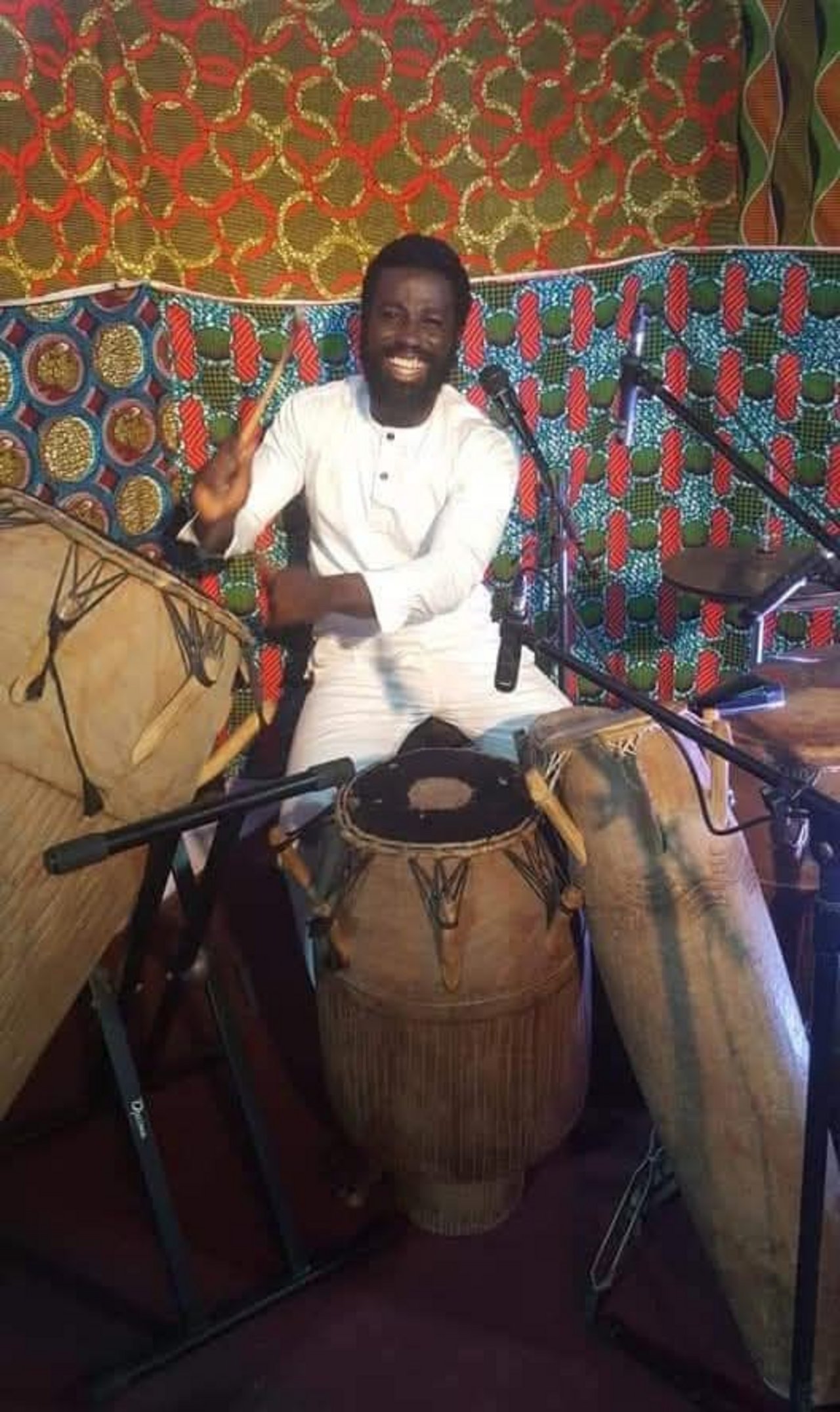

Joseph Bannor

Joseph is a Ghanaian super talented musician residing in Accra. He's got a world class touch on his traditional percussion instruments. Arranger bei Best Wave Music Technologies.

General Associate of Arts and Sciences - Juni 2001–Aug. 2023 at Modern Sciences and Arts University.

Joseph had a passion for music since age 8 and pursued it professionally after completing school. He played in a band with his friend Peter Somuah before the latter set off for Europe, where he really took off and is now a multi-award-winning jazz great.

His notable milestones include:

- Pan-African Youth Orchestra (PAYO)

started here and showcased his talent among young musicians from diverse Ghanaian backgrounds.

- Pan-African Orchestra (PAO):

his skills earned him a promotion to this renowned orchestra, known for blending African traditional and neo-traditional sounds. The PAO, founded by Nana Danso Abiam in 1988, features instruments like atenteben flutes, gyile xylophones, kora harp-lutes and gonje fiddles.

Joseph later joined this Ghanaian gospel group, which had a global hit album and performed alongside American gospel artists. The band's lead, Kenneth Appiah, is a composer and Afro-pop performer from Accra.

Then to the Gh jazz collectives with notable names like Victor Dey jnr, Bernard Ayisa. Got the chance to play also with Etienne Mbappe, Sean Nowell, Nicolas Genest, Bruce Harrisand more.

Now, Joseph is leading his own band, blending local folk songs with international genres, incorporating up to 80% Ghanaian drums and showcasing strong vocal skills.

With a new album on the horizon, his musical journey continues to evolve.

Jazz Tour in Europe 2026

GIGS LIVE MUSIC VENUES

WORKSHOPS

TOP JAZZ LOCATIONS IN GERMANY

BERLIN

Kesselhaus in der Kulturbrauerei

BIELEFELD

BREMEN

DISSEN

FRANKFURT

Die Jazz-Initiative Frankfurt am Main e.V. (JIF)

Brotfabrik Frankfurt, Kulturverein 21 e.V.

HAMBURG

HANNOVER

Kulturpalast Linden e.V. - Hannover

HARSEWINKEL

FARMHOUSE Jazzclub Harsewinkel e.V.

HILDESHEIM

KUFA Kulturfabrik e.V. - Hildesheim

HOLZMINDEN

Jazz Club Holzminden e. V. - Holzminden

KASSEL

Kulturzentrum Schlachthof Kassel

KÖLN

LEER

LÜNEBURG

MARBURG

MINDEN

MOERS

JAZZ FESTIVAL für Musik, Miteinander, Freysinn und: Klangfriede!

MÜNCHEN

MÜNSTER

NIENBURG

OLDENBURG

OSNABRÜCK

RHEDA-WIEDENBRÜCK

Jazz-Club Rheda-Wiedenbrück e.V.

ROSTOCK

USEDOM

WILHELMSHAFEN

Jazzclub Wilhelmshaven-Friesland

WOLFENBÜTTEL

WOLFSBURG

JAZZ STILES

with the following approximate chronological order:

• New Orleans/Dixieland jazz (from 1900)

• Chicago jazz (1920s)

• Swing (1930s)

• Bebop (1940s)

• Cool jazz/West Coast jazz and hard bop (1950s)

• Free jazz (1960s)

• Fusion, rock jazz or jazz rock (1970s)

New Orleans/Dixieland jazz

Between 1921 and 1923, the first jazz recordings by African-American bands1) from New Orleans were made, and these are considered to be the first authentic recordings of this type of music.

However, the first styles of playing that can be considered a form of jazz are thought to have emerged as early as 1900. Jazz thus began its development with a phase lasting more than 20 years, about which only retrospective and often contradictory accounts are available. During this long period, the playing styles heard in the recordings from the early 1920s developed only gradually. By no means was a uniform style played from the beginning and then unchanged for two decades. The stylistic scheme thus begins with an unrealistic assumption.

The term Dixieland jazz is mostly used to describe the imitation of African-American playing styles in New Orleans by ‘white’ musicians.

Such ‘white’ bands were already making recordings in 1917, but only played the same style when viewed superficially.

Chicago jazz

The historically significant jazz of 1920s Chicago was primarily that recorded there by African-American musicians from New Orleans and is called New Orleans jazz after its stylistic pattern.

Initially, this was the music of King Oliver and his band, and then especially that of Louis Armstrong and his Hot Five/Seven band.

However, Armstrong's outstanding importance lies precisely in the fact that in these recordings he increasingly broke with the New Orleans style of playing with his brilliant solos and developed a new style. Ironically, the stylistic scheme does not allow for this decisive step in the development of jazz.

This is because the term Chicago jazz does not refer to Armstrong's music, but to a circle of young ‘white’ musicians who imitated Armstrong and other musicians from New Orleans in their own way. In addition, they deviated from their role models to varying degrees and in different directions, so that no uniform style emerged.

The most talented among them was considered to be the cornetist Bix Beiderbecke, who made some beautiful recordings with the similarly oriented saxophonist Frank Trumbauer in his soft, contemplative and ‘classically’ influenced style.

Some ‘white’ musicians saw Beiderbecke as a leading figure of their own ‘race,’ and as such he continues to have an impact today. However, Beiderbecke played no role in the further development of jazz, which was driven by African Americans. What the ‘white’ so-called ‘Chicagoans’ produced was therefore neither a consistent style nor a contribution to jazz history significant enough to justify attributing the 1920s to them. With its focus on the Beiderbecke circle, the stylistic scheme also overlooks the significant developments in New York.

There was a lively scene of virtuoso stride pianists there, and Duke Ellington made his first recordings with a jazz big band towards the end of the decade, which are still significant today.

There was a lively scene of virtuoso stride pianists, and towards the end of the decade Duke Ellington made his first recordings with a jazz big band, which are still significant today.

Swing

The long-standing dominance of “white” musicians, based on racism, was also reflected in the stylistic patterns of the 1930s. Swing was a successful dance music trend that began in 1935, initiated and led by ‘white’ big bands, especially Benny Goodman's. It was based on watered-down African-American playing styles and gave African-American bands only limited opportunities to perform. 6) By focusing on this swing fashion when looking at the 1930s, the stylistic scheme follows commercial considerations, whereas it should focus solely on the development of jazz in terms of its own special qualities. 7) The musically significant innovations did not take place on the Goodman/Glenn Miller track with its American way of life flair. Duke Ellington's music was never swing, and it developed from the mid-1920s onwards without ever changing from one style category to another. The same applies to Fletcher Henderson's band, and the particularly elegant and strongly swinging, blues-laden music that Count Basie's band brought with them from Kansas City is also misunderstood when perceived in the context of swing clichés. Pianists such as Earl Hines and Fats Waller did not change their playing style after the so-called swing era began in the 1930s. They were seamlessly connected to predecessors such as James P. Johnson and Willie ‘Lion’ Smith, who were already significant in the 1910s. No stylistic category can capture the musically significant recordings of the 1930s as a more or less uniform type of music and distinguish them from their predecessors. For example, what commonality should the Basie band have had in the 1930s with Art Tatum's solo recordings that it did not also have with Ellington's, Earl Hines' and Armstrong's music of the 1920s? Viewing the diverse developments in their continuity without arbitrary stylistic distinctions yields a much more realistic and vivid picture.

Bebop

Around 1945, fans of popular swing music must have had the impression that the first recordings by Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker, which were released at that time, were a completely new, revolutionary type of jazz.

This new music is called bebop in jazz literature and is often understood as the first form of ‘modern’ jazz, as it no longer offered a popular form of entertainment but demanded attentive listening.

However, the abrupt shift from entertainment to listening is only apparent when bebop musicians are contrasted with popular swing big bands such as Benny Goodman's.

In fact, long before that, many jazz performances required attentive listening, for example Louis Armstrong's solos, which he presented in Chicago in the 1920s, the stride pianist competitions in Afro American bars and at rent parties in New York, Duke Ellington's ambitious compositions in the 1930s, pianist Art Tatum's solo improvisations in various venues, and the sophisticated interpretation of the song Body and Soul in tenor saxophonist Coleman Hawkins' 1939 recording. From the mid-1930s onwards, a number of thriving venues sprang up on 52nd Street (near Broadway) in New York, where small bands played jazz for a predominantly ‘white’ audience to listen to (not to dance to).

At that time, there must have been a sufficiently large number of jazz fans in New York who understood this music as an art form worth listening to, which was mainly due to the influence of the hot clubs of the time and a number of jazz critics. Jazz fans were particularly attracted to the so-called jam sessions, which were considered especially authentic, and so the clubs on 52nd Street staged simulated jam sessions by well-known musicians. The desire for jazz that was as authentic as possible and not commercially adapted paved the way for the emergence of bebop musicians. From the mid-1940s onwards, they and their bands were booked to play on 52nd Street, and their frequent collaborations with more traditional musicians, especially the tenor saxophonist Coleman Hawkins, who was considered a swing musician, helped them to build an audience.

Musically speaking, bebop musicians also built largely on the achievements of their elders. Their music was characterised by an enhancement of essentially existing qualities, not by fundamentally new ones. What many at the time saw as a break with tradition has long since been recognised as an organic development. The distinction made by giving it its own name (bebop) obscures its connection to its predecessors. This connection does not contradict the fact that the young musicians developed their own playing styles and personal expressions in very creative ways. Charlie Parker exerted a strong influence with his loose, flowing, smooth and sophisticated melodic lines, and others also became role models. Certain forms of interaction also became established in their bands. However, the leading representatives of the bebop movement developed a distinct individual character. For example, the playing styles of the two most important pianists of the bebop movement were fundamentally different, as the following statement by Miles Davis makes clear: "Many people said that [Thelonious] Monk couldn't play the piano as well as Bud Powell because they considered Bud to be the better technician due to his speed. It's complete nonsense to judge them on that basis, because their styles were completely different. [...] Both were incredible pianists, they just had different styles." Forcing the personal styles of Monk, Powell and others involved in this circle of musicians into an overarching style category called bebop unnecessarily broadens the view. Attempts to describe bebop on the basis of characteristics remained correspondingly vague. They largely exhausted themselves in a presentation of superficial aspects and the observation of greater complexity in most musical aspects. But the music of Art Tatum, John Coltrane and Steve Coleman is also complicated, without them being regarded as bebop musicians.

The most distorting effect of the bebop categorisation is the equation of the original with simplified imitation: playing Charlie Parker's music learned from transcriptions is something completely different from Parker's highly creative, profound, artful and personal work. To describe both as one and the same thing, namely as bebop, is therefore a massive distortion. Parker's brilliant musical ‘storytelling’ was thus detached from his person and turned into a kind of formulaic commodity that can be copied at will. Those who imitate Parker do not play bebop like Parker, but merely imitate Parker.

For a few years, the bebop movement received considerable public attention, probably because jazz in the form of swing and Dixieland was popular and bebop appeared to be a sensational, albeit problematic, new form of jazz. By the end of the 1940s, its appeal as an irritating novelty had apparently faded, its potential as a protest culture for ‘white’ youth had been exhausted, and its lack of profitability had become obvious. Public interest evaporated and jazz critics declared the end of bebop. However, the musicians did not stop playing; on the contrary, many younger musicians joined them (including Sonny Rollins and John Coltrane) and the bebop movement gradually began to exert a lasting influence on many areas of jazz.

Max Roach said in the 1970s: "We live in a society where you have to have a new car every year and a new model of this and that. [...] And that's exactly how it is when a new fashion is introduced: whatever was popular before is simply declared “out” or dead. I never felt that the music of the 1940s was dead. I believe that it lives on and on [...]. The people who created and developed all of this, people like Art Tatum, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker and Bud Powell, are still the driving force behind everything that happens. So much happened musically during that period that everyone is still living off it today, and the things on the scene today that don't relate to it, you can forget about them, they fade into insignificance. John Coltrane was a further development of the things from the 1940s, McCoy Tyner, Rahsaan Roland Kirk, all of them."

Cool jazz/West Coast jazz

According to influential German jazz critic Joachim-Ernst Berendt, jazz became ‘cool’ around 1950, and Italian jazz critic Arrigo Polillo titled a chapter in his history of jazz ‘Jazz Becomes Cool’. However, around 1950, the significant innovators of the 1940s (Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Bud Powell, Max Roach, Thelonious Monk, etc.) did not begin to play ‘cool’ by any means, nor did they stop playing. The same applies to many older musicians such as Duke Ellington, Art Tatum, Coleman Hawkins and the revived Dixieland jazz, which was popular with many listeners. Rather, the following happened around 1950: the topic of bebop, which was treated superficially in the media, exhausted itself without this music having gained a larger serious audience. It also remained difficult to access for many jazz critics. Polillo even described Parker's playing style as ‘morbid’ in 1975. At the end of the 1940s, influential critics were particularly attracted to musicians who, while building on the innovations of the bebop circle, steered their music in the direction of European classical aesthetics. Critics coined the term ‘cool jazz’ and praised this direction as the most modern and artistically sophisticated jazz style. Berendt immediately discovered his ‘love of coolness,’ as he put it. He was the first European to contact Lennie Tristano, the ‘high priest of cool jazz,’ dedicated a separate chapter to him in the first edition of his jazz book (1953) as the most important jazz musician after Charlie Parker and declared that cool jazz would become the style of the 1950s. Over the years, Berendt brought many cool jazz musicians and those of the ‘West Coast jazz that emerged immediately afterwards’ to concerts in Europe.

In the 1959 edition of his jazz book, however, Berendt then found that it was now possible to ‘write about jazz more objectively and independently of developmental trends’ and that perspectives had emerged that were ‘in some respects the opposite of what one read in jazz magazines at the time’ when ‘Lennie Tristano had the last word’. 39) Tristano was now ‘not dismissed,’ but he no longer had his own chapter. Berendt's portrayal of jazz in the 1950s became confusing: ‘After Tristano’ (as if Tristano had already died at that time), the focus had shifted to the American West Coast, to ‘West Coast jazz.’ But experts had repeatedly pointed out that New York was still the real capital of jazz, and West Coast jazz had been contrasted with East Coast jazz. However, it now seemed to be proven that both West Coast jazz and East Coast jazz were less stylistic terms than sales slogans used by record companies. The real ‘tension in the development’ was not a ‘tension between the East and West Coasts, but rather between a classicist direction on the one hand and a group of young musicians, mostly black, who played modern bebop on the other.’ However, Berendt also claimed that the ‘cool concept’ had dominated ‘all jazz’ of the 1950s in a limited sense. In later editions of his jazz book, he stated that cool jazz had been the ‘dominant’ style until the mid-1950s. Other authors believed that the heyday of cool jazz had already ended in 1953 or had never really come about at all. It also remained unclear which musicians could be counted as cool jazz, and ultimately the term cool jazz itself proved to be a nebulous concept that largely evaporated upon closer inspection.

Hard bop

In the mid-1950s, the term ‘hard bop’ appeared in jazz journalism and played a role in the debate mentioned by Berendt among jazz critics about the dominant “white” ‘West Coast jazz’ and the less noticed African-American jazz on the ‘East Coast’ (New York). The ‘white’ aesthetic, which tended towards smoothness and the European idea of sophistication, was perceived as softer and cooler, while the aesthetic more closely associated with African-American traditions was perceived as harder and more vital. Meanwhile, the West Coast/East Coast debate is long past, and the African-American line of development leading from Charlie Parker to Sonny Rollins and John Coltrane has established itself as the centre of the jazz tradition. However, the now superfluous term ‘hard bop’ has become established as a supposed ‘jazz style’ and is used with varying, rather arbitrary meanings. According to Mark C. Gridley's book Jazz Styles (2012), considered the most widely used introduction to jazz history in the United States, hard bop can be used to describe at least the following four styles of jazz from the 1950s and 1960s:

• a gradual continuation of bebop, often indistinguishable from the music of its founders (for example, the music of Clifford Brown, Max Roach and Sonny Rollins),

• an easily singable, bebop-based music also known as funky jazz and soul jazz, which contains melodies with a bluesy, gospel-like character accompanied by simple, constantly repeating figures (some of them from Latin America) (e.g. some songs by Horace Silver and the Adderley Brothers),

• a strongly driving later development that has its roots in bebop and often contains the following: a) pieces based on their own chord progressions, not those of pop songs [as is common in bebop], b) improvised lines that differ from the preferred phrases of Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie (for example, the music of Art Blakey's band of the 1960s and the Art Farmer/Benny Golson Jazztet; some authors would also include the bands of Miles Davis in the late 1950s and early 1960s, with the exception of the album Kind of Blue),

• a new approach that emerged in the 1960s, which is not entirely free of bebop, but is mainly based on its own concepts, which were not part of the free jazz movement of the time; this style group is very diverse and has not been given its own name (for example, the music of Wayne Shorter, Joe Henderson, McCoy Tyner, Herbie Hancock and Freddie Hubbard) – Another example is the recording Masqualero (1967) by the Miles Davis Quintet, but most musicians would not call it hard bop, but simply ‘mid-60s Miles Davis’ style. Many Davis recordings would typically be classified as cool jazz, not only Birth of the Cool, but also the recordings from the early 1950s with Sonny Rollins, Horace Silver, Milt Jackson and others. Some would even describe his album Kind of Blue (1959) as cool jazz, although it fits more into the hard bop or modal jazz category.

In John Fordham's The Great Book of Jazz, even John Coltrane's Giant Steps (1959) and Thelonious Monk's Brillant Corners (1956) are cited as examples of hard bop. Yet the Giant Steps album, with its complex harmonic structures, is the very opposite of the simple soul jazz songs mentioned by Gridley in his second point, and Monk's music in the 1950s was not significantly different from before, when he was still considered a bebop musician. Ultimately, hard bop is little more than a confusing convention.

Free jazz

The tradition represented by musicians such as Art Tatum and Charlie Parker is very demanding, so that only a few musicians have succeeded in making significant creative contributions to it (such as Sonny Rollins) or even taking it in a new direction, as John Coltrane did. However, at the end of the 1950s, Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor demonstrated a possible liberation from the oppressive role models of tradition. Their example encouraged many musicians in the 1960s to experiment with unconventional musical possibilities and forms of expression, and the idea of freedom from established musical rules and expectations inevitably gave rise to a particularly wide spectrum of different playing styles. The only reliable commonality between these playing styles is that they represent more extreme areas of music that only a few listeners enjoy. But that alone does not justify considering them stylistically similar.

It is particularly misleading to equate the 1960s with free jazz, because at that time a wide range of jazz forms were being played, and although free jazz was debated, it was rarely performed due to a lack of demand in the USA. Coltrane's magnificent recordings from the first half of the 1960s are not free jazz, nor are those of the Miles Davis Quintet from 1963 to 1968. It is precisely these recordings by Coltrane and Davis that had the strongest influence from the 1960s on subsequent generations of musicians. The fact that they still do not fit into the stylistic scheme shows once again how questionable it is. Some authors have attempted to capture these important recordings with another stylistic category called modal jazz. However, the term modal has a dazzling spectrum of meanings in jazz, and recordings in which modality plays a role do not necessarily have to be stylistically similar and can differ greatly from one another.

Fusion

Jazz has always developed in several directions. On the one hand, artful, increasingly sophisticated and ultimately difficult-to-enjoy styles of playing gradually emerged, while on the other hand, the transition to more popular music offered opportunities to reach a wider audience. The aforementioned soul/funky jazz already featured rhythms and sounds from rhythm and blues. Around 1970, Miles Davis began to use the ‘electric’ sounds and rhythms that were popular in the music of young people to create avant-garde-style soundscapes that represented a clear stylistic break with his earlier music. Some of his former band members followed his example with their own groups, moving even closer to popular music. This music, initiated by Davis and aimed at a large young audience, seemed so novel that it was obvious to create a separate style category for it called fusion (rock-jazz/jazz-rock). However, the fusion of jazz playing styles with elements from other genres of music was soon practised in such diverse ways, and ‘electric’ instruments and funky rhythms were used so naturally in other contexts, that the contours of the newly created category became blurred. It has long since ceased to make sense to identify a change in style category when a band uses an electric bass instead of a double bass or a keyboard instead of a piano (perhaps because the latter is not available), when an electric guitar is not played with the slender tone of a Wes Montgomery, or when rhythms sound funky. Only in relation to certain playing styles that clearly reflect the rock-jazz spirit of the early 1970s does the term fusion still seem appropriate.

In the 1970s, fusion was the most commercially successful type of jazz, but by no means the only one, nor the most musically significant. From a jazz perspective, other recordings from the 1970s are much more interesting, for example the music of McCoy Tyner, Woody Shaw, Von Freeman and members of the AACM musicians' cooperative.

End point

The style scheme thus highlighted a particular development for longer periods of time that jazz critics considered particularly significant. In retrospect, their selection (as presented) is largely questionable, and from 1980 onwards, critics were no longer able to identify a distinct ‘style’. Attempts were still made to derive two contrasting styles for the 1980s and 1990s from the conflict between Wynton Marsalis's traditionalist line and those with different orientations, which was widely reported in the media. However, there have always been those who preserve tradition and those who are open to new ideas, and their differences of opinion are sometimes more, sometimes less, the subject of media coverage. Traditional approaches are characterised by the fact that they do not produce any new styles, and the openness of the opposing position alone does not result in a common style. Therefore, attempts to form new style categories from the controversy surrounding Marsalis remained particularly vague. In addition, stylistic diversity was repeatedly emphasised as a characteristic of contemporary jazz. But that is not new either. It simply increased inevitably in the course of jazz history through the countless attempts by musicians to develop their own styles and find market niches. What was new after the 1970s, however, was that it was no longer possible to continue the long-questionable construction of a sequence of ‘styles’.

AFROBEAT

Afrobeat (Afrofunk) is a West African music genre that combines influences from Nigerian (e.g. Yoruba and Igbo music) and Ghanaian (e.g. Highlife) music with American funk, jazz and soul influences.

Afrobeats, a combination of sounds that originated in West Africa in the 21st century, is to be distinguished from Afrobeat. With various influences, Afrobeats is an eclectic combination of genres such as hip-hop, house, jùjú, ndombolo, R&B, soca and dancehall.

Although the two genres are often mixed together, they are not the same thing.

Many jazz musicians have been attracted to the Afrobeat genre. From Roy Ayers in the 1970s to Randy Weston in the 1990s, collaborations have resulted in albums such as Africa:Centre of the World by Roy Ayers, which was released on the Polydore label in 1981. In 1994, the American jazz saxophonist Branford Marsalis included samples of Fela's ‘Beasts of No Nation’ in his album Buckshot LeFonque.

AFROFUSION

is a dance and musical style that emerged between the 1970s and 2000s.

This musical style invokes fusions of various regional and inter-continental musical cultures, such as jazz, hip hop, kwaito, reggae, soul, pop, kwela, blues, folk, rock and afrobeat.

As a genre and musical compositional form, Afro fusion incorporates traditional African music, alternative music as well as Afropop, blending various genres in an experimental crossover-like style. Afrofusion songs often include vocals in a range of African languages alongside other languages such as Spanish, English and French. For example English, isiXhosa, Duala and Spanish in the multilingual song "Waka Waka".